But eventually she found an address for one Winifred Watson in Newcastle from 1974 and telephoned, on the off-chance that someone might know where the author was. Researching Watson’s life proved hard there was precious little information about her as Methuen’s records had also fallen victim to the war. She remembered her mother’s favourite book, took it along to the publisher’s office and they asked her to write an introduction. The academic came across the story when Persephone Quarterly magazine asked for recommendations for books to publish. Of course, the fact that she came to speak to Twycross-Martin at all is a good indication of a happy ending. “You can’t write if you are never alone,” she later told Twycross-Martin. This stopped her from producing any more novels. When her house in Jesmond (she spent almost her entire life in the suburbs of Newcastle) was bombed, she and her young family had to move in with her mother. She released a novel called Leave and Bequeath in 1943 (“part murder-mystery and part psychological study set in a contemporary upper-class milieu in London and the home counties,” according to Twycross-Martin) – but that was the last one. “I wish the Japanese had waited six months.” At least the experience hadn’t deprived her of her impish sense of humour.īut the war did effectively end her writing career.

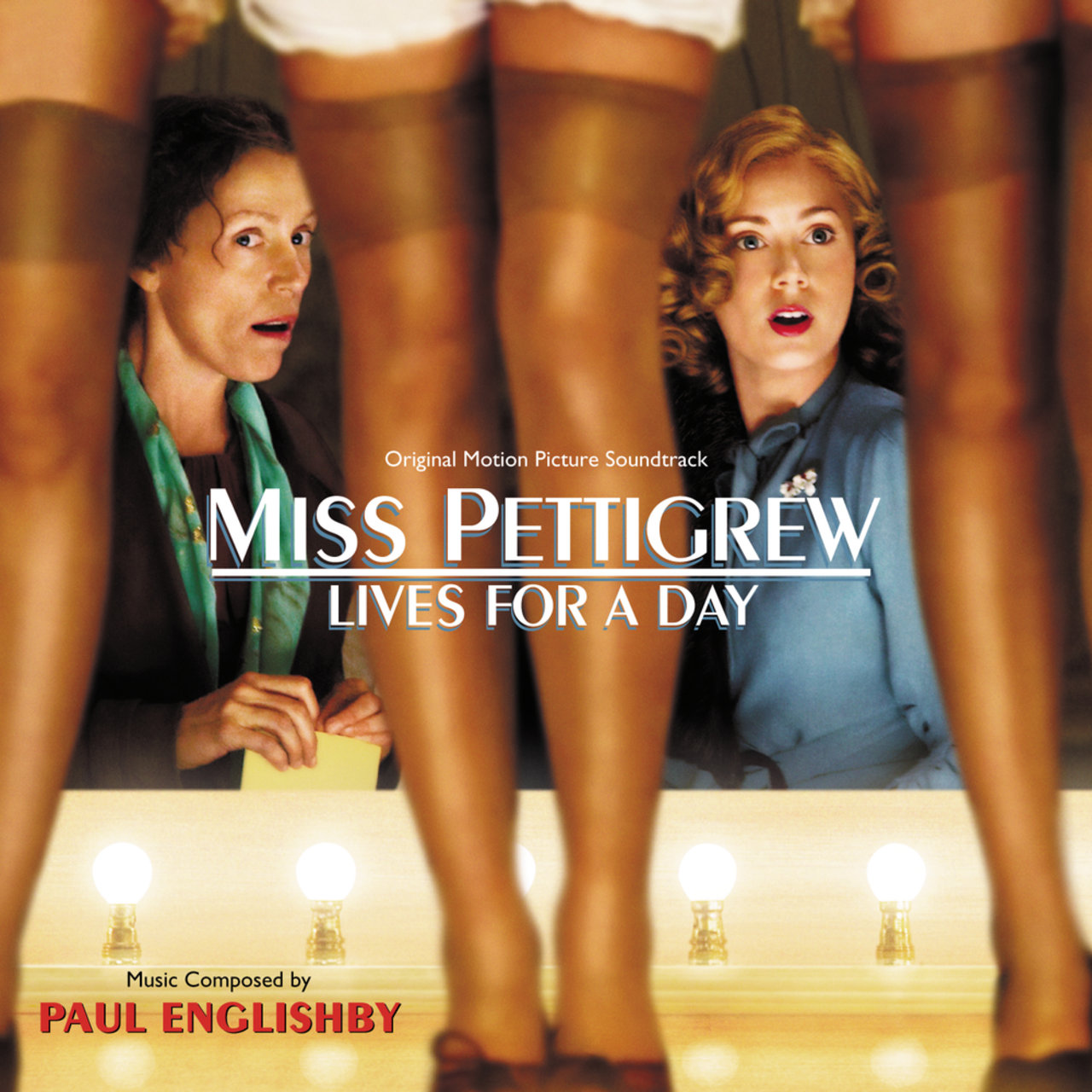

“It was a disappointment,” Watson said years later. Miss Pettigrew didn’t fit the bill, no matter how cheering it might have been. The French translation didn’t make it into shops thanks to the German invasion, while the film never happened because Hollywood studios were now focused “on making morale-boosters”. Billie Burke, fresh from starring in The Wizard of Oz as the Good Witch of the North, was lined up to play Miss Pettigrew. It was translated into French, and the film rights were sold to Hollywood.

Initially – as noted – Miss Pettigrew was successfully brought to publication in 1938 and sold well, both in the UK and the US.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)